Milan Grabovac lines up three bottles on the table in front of us. One doesn’t have a label. Another is a magnum. “I have a story about this one,” he says, gesturing to the naked bottle.

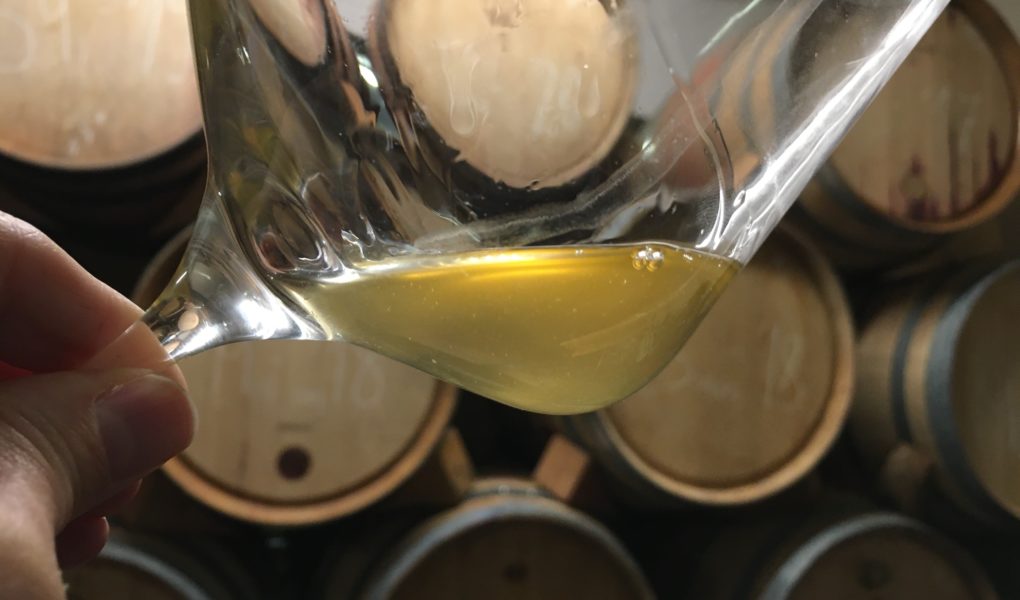

The first wine he pours is the Grabovac winery 2016 Kujundžuša. Although the Kujundžuša grape is white, this wine is the color of Cognac, an amber-gold that suggests grain more than grape. The flavors are magical—not green apples, lemons and wildflowers as you might expect from a fresh Kujundžuša, but instead baked apples, lemon zest and a savory caramel. It may taste like autumn baking, but it is not sweet—it’s completely dry and has noticeable tannin. If you closed your eyes you might suspect it was red. In fact, this is what white grapes turn into when you treat them the same as red grapes in the winery. Some might say, when you let them reach their full potential.

Introducing orange

For centuries, wine came in red and white. Or so we assumed. True, recently wine lovers have gone crazy for pink wine, or rosé. But it turns out wine makers in certain parts of the world have been making wine of a different hue all along. It appears orange or amber in the glass. It’s called orange wine (though it’s made from grapes) or amber wine or skin-fermented white wine.

Whatever its name, in the past 20 years it has reestablished itself as a wine style around the world. And in Dalmatia, a land where red wines may be heavy and high in alcohol, orange wine captures a broader range of flavors and textures (and yes, color) than usual from white grapes, and is more versatile than traditional reds.

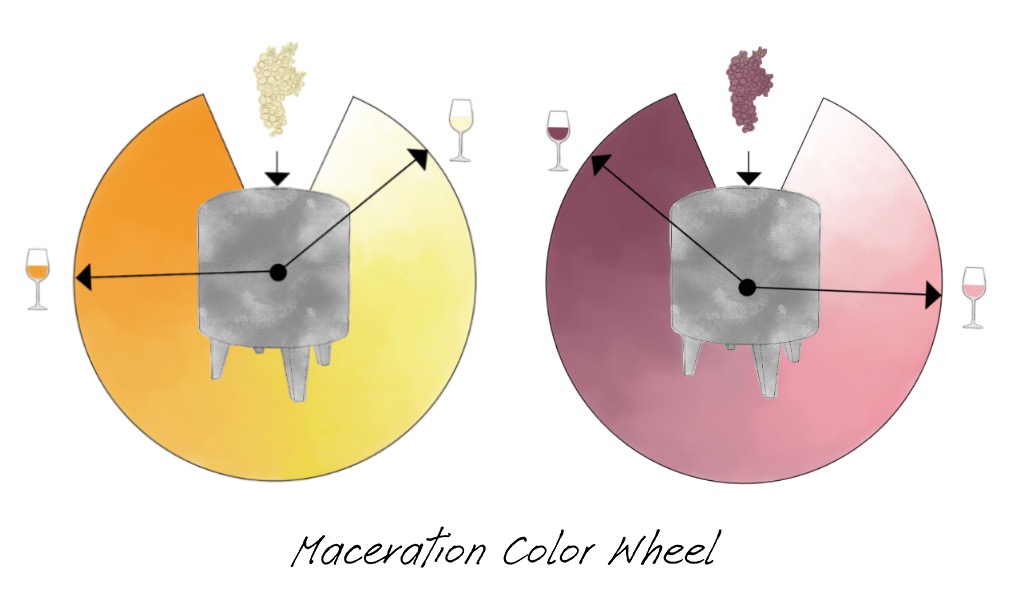

If you know a bit about wine, you know that red wine is red because the juice soaks, or macerates, with the skins during fermentation. When black grapes are crushed, the juice starts off clear, but turns red as pigment is released from the grapeskins. The skins also contain texture and aroma compounds that end up in the wine.

Rosé wine is also made from black grapes, but the juice macerates with the skins for much less time, then is separated from the skins and fermented on its own. This pre-fermentation maceration is called cold maceration—a cold temperature in the vat prevents fermentation from starting. This generally shorter maceration, and the fact that the juice is not fermented with the skins, gives rosé less flavor and color than red wine.

If texture and aroma compounds are locked in the grapeskins (and they are) it seems contradictory to make white wine in the same way as rosé—giving up some flavor by not fermenting with the skins. Nevertheless, for white wine, after an optional cold maceration to draw out some flavor, the juice is separated from the skins before fermentation.

Q: What if white grapes were given the same maceration time as red ones—what if they were fermented with the skins? A: Then, the color, flavor and texture compounds in white grape skins would be present in the wine. Then you’d have orange wine.

Success at 67 points

Grabovac pours the second wine, with no label. The first wine, the 2016, was macerated on the skins for 25 days. This second wine is the 2017 Kujundžuša, which spent 40 days on the skins. This wine doesn’t seem to have any more flavor for the additional 15 days of maceration, but it has a lot more tannin. What in the 2016 was understated is now dry-textured and a touch astringent. The 2017 also has a slightly darker amber hue. Because of its pumped-up structure, it’s a great wine to pair with food.

Grabovac launches into his story, the saga of the 2017. In Croatia, winemakers who want to use certain terminology on their label (such as Kvalitetno Vino or Vrhunsko Vino, the Croatian quality levels) are required to send each wine, in each vintage, to the Center for Viticulture, Winemaking and Oil Production in Zagreb for evaluation. A chemical analysis is done on each wine, and then it is scored on a 100-point scale by a panel of tasters to confirm that it is well made and typical of its origin, grape and style.

When Grabovac first submitted the 2017 its chemical analysis was clean, but on tasting it was rejected as oxidized. “We emphasized that it’s a traditional vinification, it’s a maceration, skin contact,” he said, but some of the tasters may not have been familiar with orange wine. He decided to submit the wine a second time. This time the tasting panel determined that the wine lacked typicity. “The score was 67, I think. And then I went completely mad.”

Already Grabovac winery doesn’t use the Croatian quality terminology on its labels. “From 2015 we decided we are not going to use the option,” said Grabovac. The quality categories are indeed optional, but the panel scores also determine whether a wine can be labeled Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), in this case indicating that the wine is typical of the Imotski region, where Grabovac is located. Because the 2017 Kujundžuša got a score of 67, it can’t even be labeled PDO.

Grabovac is clearly still irritated, but his thinking has taken a creative turn. He originally considered labeling the 2017 with a skull and crossbones, the universal poison symbol given an artistic rendering. Instead, he says, he will use the usual label for the wine, with the reference to Protected Designation of Origin X-ed out as with a typewriter. It will be a puzzle for those who read such things.

A moral for this story might be, ‘Orange wine can be misunderstood.’

Orange wine’s modern revival

The current resurgence of orange wines can be attributed to the persistence and skill of two wine makers in Friuli, Italy, and to the revival of traditional winemaking in Georgia. Joško Gravner and Stanko Radikon both rebelled against the modern, technological style of winemaking that had garnered so much attention for Friulian wine by the mid-1990s. They wanted to make wine that was true to the fruit and the region—they wanted to return, to some extent, to a time before technology.

Up to World War II, families making wine in Friuli fermented white wines just like red ones—juice, skins, seeds and all, in an open vat. The same tannins and color components from the skins that protected red wine from oxidation protected white wine as well. Made this way, the wine might even last until the next harvest. Gravner and Radikon looked to their winemaking roots, and each released his first skin-fermented white wine from the 1997 harvest. Their fellow wine makers thought they were crazy, but the wines soon gained an avid following.

Meanwhile, Georgia was slowly reviving its traditional method of making wine in large, egg-shaped clay vessels called qvevri, which are permanently buried in the ground to maintain an even, cool temperature. This is the original orange winemaking; all parts of the grape, and sometimes even the stems, are put into the qvevri to ferment. Wine has been made this way for some 8,000 years in Georgia, but the Soviet era all but erased the tradition. After Georgian independence in 1991, a civil war and a Russian embargo on Georgian wine that lasted until 2013 effectively suppressed winemaking in Georgia. But quietly, some small wine makers had preserved qvevri winemaking. They preferred the traditional, artisanal stye of wine over the factory wine that had prevailed under Russia’s domination. And word started to get out. In 2001 Joško Gravner started making wine in qvevri he had obtained from Georgia.

It’s clear that, after eight millennia, there is nothing new about orange wine. And the practice of making it was not restricted to Georgia and the northern Adriatic. “The technique of macerating white wines for days or even weeks was common all around the Adriatic and is documented in a number of books from the nineteenth century,” wrote Simon J. Woolf in his own excellent book, Amber Revolution.

Ironically, this style of white winemaking was—and still is—typical in Imotski as well. “Over here, many rural households produce their homemade wine in that style,” said Grabovac. “It extracts more antioxidants, phenols, from the grape skin and protects the wine for a longer period. That was the reason why they did it. But we like to taste wines from all over the world, and we saw it was becoming a trend. We thought okay, many locals are doing it for decades, maybe centuries. Let’s try to do it ourselves, to see how it will work. That was 2008.”

A spotlight on grape and terroir

As Grabovac pours the third wine, from the magnum, he says that regardless of maceration time, he believes these wines speak clearly of the vineyard they came from. They’re also an advanced-level seminar on the Kujundžuša grape, with their baked apple, overripe fruit, spiced citrus and bitter almond notes. This clear expression of grape and terroir may be the primary factor causing more wine makers to add an orange wine to their lineup: it’s the perfect showcase for white grapes.

Natural wine maker Denis Bogoević Marušić, at Vinarija Križ on the Pelješac peninsula, would not consider making a standard white wine. “Natural wine producers make orange wine as a way of producing white wine as it was before.” He points out that the fruity flavors we taste in conventional whites are often from added yeast, not the grapes. But “it’s the taste of the grape in the orange wine.” He adds, “If you want to taste something original and you speak about the terroir, that’s it.”

Chefs are also intrigued by the possibilities of orange. The 2016 Kujundžuša magnum is from two experimental barrels of wine that have been bottled exclusively for Pelegrini restaurant in Šibenik. This wine was made virtually the same as the previous two in our lineup—all fermented only on wild yeast, all aged in mostly used oak for 12 to 18 months, all unfiltered—but the wine for Pelegrini was macerated 144 days.

“We didn’t know what to expect,” said Grabovac. “We wanted to [macerate] for a really long time. Rudi [Štefan], the owner of Pelegrini, encouraged us to experiment with the longer skin contacts, to see how it would work.” They tasted the wine regularly during the maceration and saw the color and tannin increase. Then they saw them start to go back down and decided the wine was ready. This wine is smoother, more delicate, than the previous two. “It has a bit more finesse, definitely,” said Grabovac. Why is this 144-day maceration lighter and smoother than the 40-day version? Grabovac smiles. “It’s a paradox.”

Selected Dalmatian Orange Wines

The length of maceration, including fermentation, of an orange wine depends on the style the wine maker intends, as well as the features of each grape variety.

Ahearne Wild Skins 2018

A blend of Bogdanuša, Kuč and Pošip

Macerated 1 year (Bogdanuša and Kuč) and 10-15 days (Pošip)

Ante Sladić Oya Noya 2017

Made from Debit

Macerated 14 days

Bibich Bas de Bas 2016

Made from Debit

Macerated 90 days

Boškinac Ocu 2018

Made from Gegić

Macerated 21 days

Bura-Mrgudić Plavac Mali Sivi 2016

Made from Plavac Mali Sivi

Macerated 6 days

Divina Aurum Pošip 2017

Made from Pošip

Macerated 14 days

Duboković Moj Otok 2017, Moja B 2017, and Moja M 2017

A blend of Maraština, Prč, Kuč and Bogdanuša; varietal Bogdanuša; and varietal Maraština, respectively

All macerated 7 days

Grabovac Kujundžuša Riserva 2016

Made from Kujundžuša

Macerated 25 days

Krajančić ‘2012’ and Macerated 2016

Made from Pošip

Macerated 100 days and 48 days, respectively

Križ Grk 2019

Made from Grk

Macerated 5 days

Madirazza Traditional Orange 2019

Made from Grk and Pošip

Macerated 75 days

To visit wineries mentioned in this article, see our Winery Finder Tool for Dalmatia.

[Title photo: Grabovac 2020 Kujundžuša Riserva barrel sample. Photo: Staff/CCM]

One thought on “In Dalmatia, Orange Is the New Red”